Damaged areas of the brain could explain confusion in dementia patients

According to SINA Press, the cause of the confusion that people with dementia experience when something unexpected happens could be down to a specific network in the brain. New research has developed our understanding of these neural connections, and will help patients and their loved ones better manage situations that are potentially upsetting.

A new study by doctors and researchers from universities in Cambridge and Oxford compiles a decade’s worth of data to reveal how changes to the brain in dementia patients, including those with Alzheimer’s, affect their reactions to novel scenarios.

To do this, they used a technique called magnetoencephalography, which can scan the brain 1,000 times per second. This allowed them to see exactly how a person’s brain should respond to an unexpected event, and compare it to the brain of a dementia patient.

“This is called the mismatch negativity test, where you can put people in a scanner and then play the same stimulus – here we use a beep as an auditory stimulus – lots of times and then occasionally change it,” said Dr Thomas E Cope, one of the study’s authors at the MRC Cognition and Brain Science Unit and Department of Clinical Neurosciences at the University of Cambridge.

“Then, when you change it, the brain responds to that change.”

In the test, the change could just be a different pitch of note, or a new rhythm. How the brain responds to this, though, works in the same way as any real-life surprise, like a change of topic mid-way through a conversation, or the room’s furniture being moved around.

In a healthy brain, the response is in two phases. The first correlates with the auditory system “noticing the sound”, said Cope, while the activity that follows is a different area of the brain recognising the difference. “The brain reacts when it knows the sound was different. [The brain tells you to] pay attention to it, think about it, see what you need to do with it.”

But in patients with dementia, Cope and the team found a reduction in the second phase. Their brains weren’t telling them that there had been a change, and it was not telling them what to do about it either.

This could be why many people with dementia struggle when unexpected events occur.

“If people with Alzheimer’s disease are in their home environment and they’re surrounded by things they are used to, they’re alright really. They can muddle along. But then if one day something small changes – the kettle’s broken, say – and they need to respond differently, they can’t. They just can’t work out what to do.”

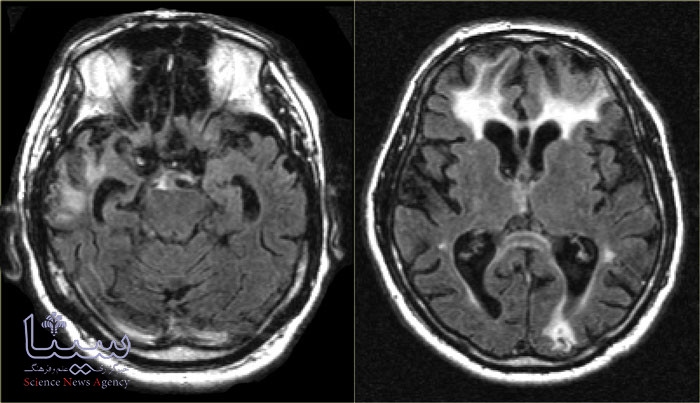

Using magnetoencephalography combined with more familiar MRI scanning, the team showed that this second phase lay in specific areas of the brain, which together make up something called the multiple demand network.

“These are all the bits of the brain that are much bigger in us than in animals like dogs and rats,” said Cope. “Though our vision cortex and our auditory cortex is about the same as that in a dog, our ‘thinking bits’ of the brain, the intelligence networks, are the ones that have got massively bigger in us.”

Cope said this multiple demand network has also been shown to be affected in patients with schizophrenia.

“In dementia syndromes, at least one of the areas in the multiple demand network is damaged or shrunk. Whereas in schizophrenia, they’re not damaged or shrunk, they’re just not connected properly. And we know those patients also have this reduced ability to respond to change. So, I think our results probably explain that as well.”

According to SINA Press, while there is no treatment that can repair or replace a person’s multiple demand network, Cope said the findings will help patients better understand what is happening to them, and how they can make change easier.

“What I say to my patients and their relatives in clinic is: we know that you’re going to struggle, particularly when things change.

“Now that may be as simple as when you’re in the middle of a conversation and then suddenly start talking about something else, and your relative will get lost because they won’t realise that you’ve moved on to a new topic.

“It’s really important to just recognise yourself whenever there’s a change, and to then signpost that very clearly. Help them through that change. And try to understand why the brain is having a problem with responding to change.”

Cope said he also recommends guiding patients to a more familiar activity when something unexpected happens.

“You say, OK, the kettle’s broken, but we don’t need to fixate on that. Let’s move on and make some toast or something, because, the toaster is not broken and that might be a routine or something else that they’ve practised.”

Source: sciencefocus